Today, we welcome back our most frequent guest poster, Alex Macris. Over the past week, we’ve all seen the mainstream media analysis and FinX hysteria screaming that President Trump has no idea what he’s doing as he intentionally destroys the economy with poorly thought-out tariffs. Last week, DKI asked the question, “Tariffs – What if Everyone is Wrong?“.

In his usual detailed analytical style, Alex answers the question by explaining what the President is thinking. In his piece “Balanced Trade”, he describes the reasoning behind the tariffs and how the tariff levels were calculated.

Alex has kindly offered Balanced Trade to DKI as a guest post. I recommend it to all, but especially to the people who disagree with the President’s tariff policy. You’re still welcome to disagree, but I think it’s valuable to understand the thinking behind the policy.

On Thursday at 2pm Eastern Time, Alex, new DKI analyst, Matt Pettit, and I will be discussing the Trump tariffs and focusing on the aspects of the policy we think most people are misinterpreting. DKI free subscribers are welcome to watch the livestream on X at https://x.com/Gary_Brode and on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/@DeepKnowledgeInvesting.

DKI premium subscribers and Tree of Woe subscribers will receive the details to log into the Zoom call directly where they can submit questions.

Balanced Trade first appeared on Contemplations on the Tree of Woe. That’s Alex’s blog. At DKI, we try to stay emotionally neutral to facilitate rational trading and investing. However, if you’re having too good a day and want some concerning analysis to complete your daily requirement of woe, I recommend reading Alex’s work. He even offers microdespair, but I think that’s at an additional charge.

Balanced Trade

Understand the Method Behind the “Madness” of the Liberation Day Tariffs

A central part of President Trump’s 2024 election campaign was his pledge to make place tariffs that would raise revenue, protect American manufacturing, and restore balanced trade to our global economy.

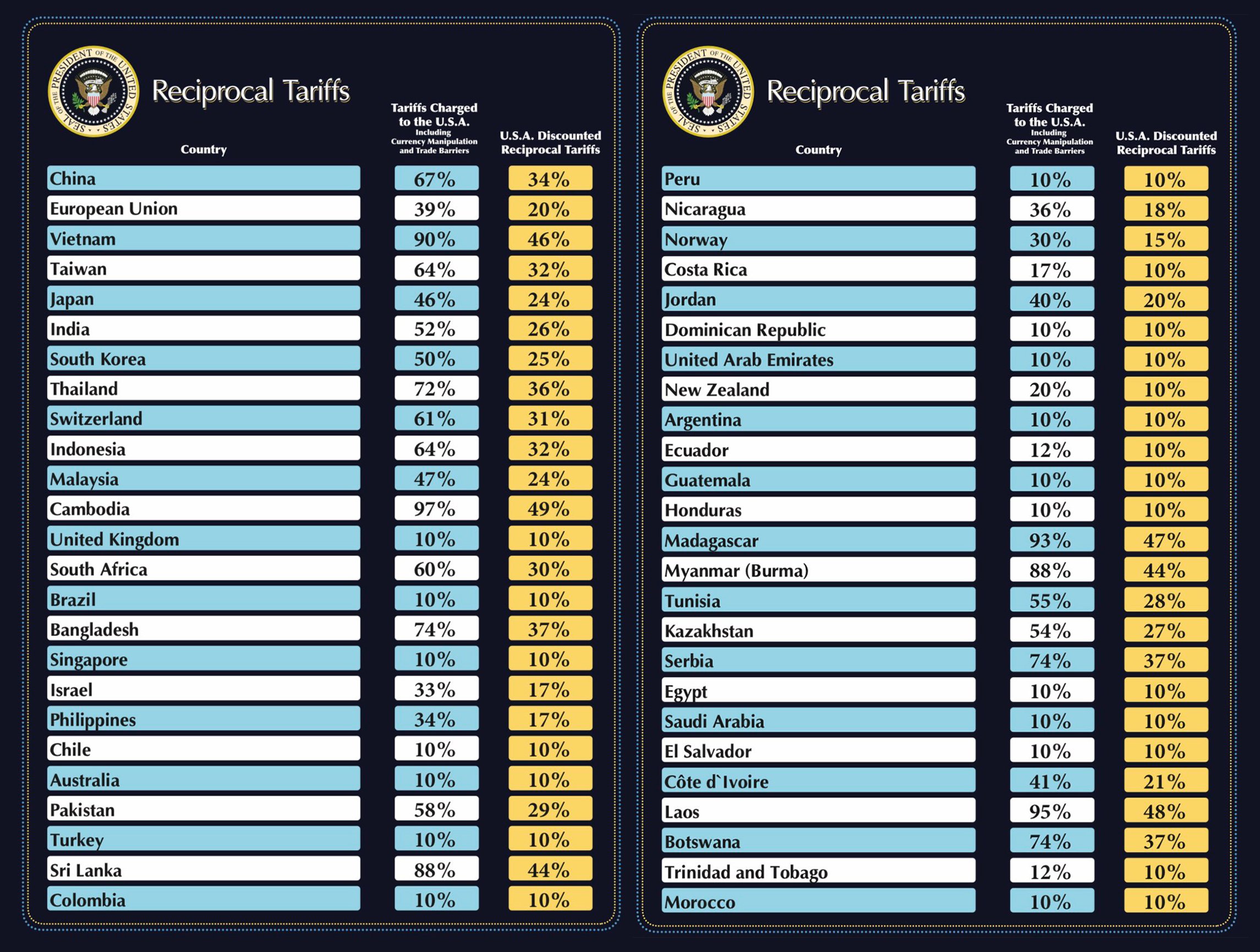

On April 2,2025, a day he dubbed “Liberation Day for American trade,” Trump made good on this promise. His executive order “Regulating Imports with a Reciprocal Tariff to Rectify Trade Practices that Contribute to Large and Persistent Annual United States Goods Trade Deficits” places a duty on all imports from all trading partners that starts at 10% and increases to rates as high as 50%.

Soon after the unveiling of Trump’s executive order, the forces of neoliberal globalism orchestrated a counterattack of such rhetorical fierceness and economic malignity that it is virtually unparalleled in the history of fiercely malign economic rhetoric.

A mere summary of what has transpired does not suffice to understand exactly how outraged, and how outrageously uninformed, Trump’s critics are. For instance, Wikipedia blandly reports:

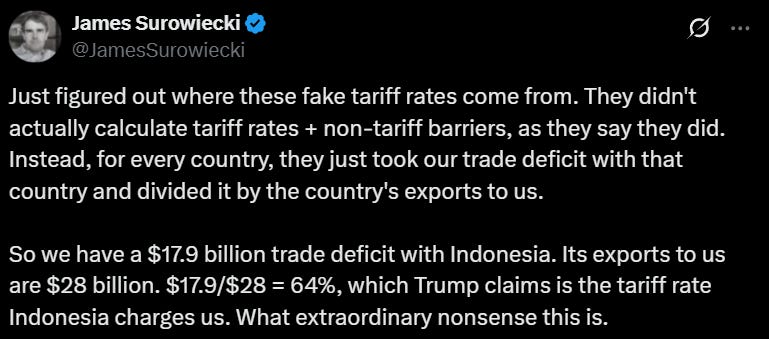

Financial journalist James Surowiecki reported that the final “reciprocal tariff” policy appeared to calculate the value of a country’s trade barriers by taking the US trade deficit with that country and dividing it by the value of the country’s exports to the United States. The “reciprocal” tariff rate Trump imposed was then calculated by dividing that value in half.

But what Mr. Surowiecki actually said was:

Ah yes — “fake tariff rates” based on “extraordinary nonsense” because “they just took our trade deficit with that country and divided it by the country’s exports to us.” But what if the only thing that is “fake” is Mr. Surowiecki’s credibility? What if the only thing that is “extraordinary nonsense” is this tweet? What if its “just” sad that people like him get treated as experts worthy of documentation in Wikipedia? What if? Heh.

Let’s start with the obvious. Yes, the Trump administration set tariff rates by dividing the country’s exports by their trade deficit with us and dividing by two. The White House has already confirmed this. It has actually published their trade barrier formula online and while their formula includes a measure of elasticity, it largely simplifies as above.

So why do I have unkind words for Mr. Surowiecki and the other critics? Aren’t they “right”? No, no they are not. They are mocking what they do not understand. The outrage of the last 48 hours has simply demonstrated that the world’s “economic experts” are illiterate in their own field.

They literally haven’t read the book that provides the theoretical basis for Trump’s tariffs.

The Theoretical Basis for Trump’s Tariffs

The theoretical basis for the Liberation Day tariffs can be found in the book Balanced Trade: Ending the Unbearable Cost of America’s Trade Deficits. Written in 2014 by three economic professors, Jesse Richman, Howard Richman, and Ryamond Richman, the book challenges the orthodox theory that free trade is always beneficial and argues for an alternate policy they call balanced trade. The authors write:

The key problem is mercantilism—the ancient and continuing efforts of countries to twist mutually beneficial international trade to a one-sided advantage. The fundamental answer we seek in these pages is how a principled country—which believes in the benefits of mutually beneficial trade—ought to respond to the predations of mercantilist trading partners.

Neoclassical economists agree that the science is settled and that free trade is safe and effective against mercantilism. But the Richmans reject the neoclassical consensus on this issue:

Economists invariably “prove” the benefit of unilateral free trade with examples in which trade is in balance. They never consider what would be the effect of unilateral free trade upon a country running trade deficits that are intentionally caused by its trading partners.

Our massive trade deficit is destroying significant segments of American industry and eliminating badly needed jobs. This is happening because we are slow to recognize an unpleasant reality: We do not live in a world of textbook free trade. We live in a world where our trading partner China has chosen mercantilism and is using the full powers of its government to advance its industries in ways that destroy ours. If we continue to turn a blind eye to this reality we will become a poor nation. However we can deal with our trade deficit; we can balance trade.

They reject the notion that unilateral free trade is justified by the benefits to consumers:

Another argument brought up by those who favor unilateral free trade is that mercantilism hurts its own consumers and helps the consumers of its victims. Therefore, the United States should appreciate what mercantilists are doing for us.For example Harvard political economy professor Dani Rodrik (2013) argued that even though mercantilism works and is practiced by state-capitalist (fascist) governments, the liberal capitalist governments of the west should do nothing to oppose it. “Liberalism and mercantilism can coexist happily in the world economy. Liberals should be happy to have their consumption subsidized by mercantilists.”

The main trouble with this argument is that it is short-sighted. Although the victims of mercantilism do get increased consumption in the short run, they pay for that increased consumption with their industries and financial assets. In the long-run they get stagnant economies, financial crises, and reduced consumption.

And they argue that mercantlism isn’t abandoned because it doesn’t work, but because it works so well it becomes no longer necessary:

Many economists assume that mercantilism is just a developmental strategy —that it will eventually be abandoned by its practitioners once they develop… It is true that mercantilists eventually abandon mercantilism. Mercantilism becomes pointless once their trading partners are too poor to be able to buy more imports than exports or once trading partners refuse to cooperate.

But the fact that countries eventually give up mercantilism after destroying the economies of their trading partners is cold comfort to their trading partners. Spain never again was a world power, the Dutch never again led Europe in technology and trade, Britain is now a shadow of its former self, and the United States may never fully recover.

They provide a game theoretic explanation of why mercantilism beats free trade, even while trapping the free traders into continuing to trade with the mercantilists.

Trade policy making is often modeled as a prisoner’s dilemma between countries, and sometimes modeled as a coordination game. But typical treatments of trade negotiations make it too easy to ignore the strategic context of responding to mercantilism.

What both coordination and prisoner’s dilemma approaches make too easy to ignore is the potential for unequal equilibria in which both trading partners gain enough from trade to make semi-free trade preferable to protectionism, but one trading partner manipulates the terms of trade to capture much more of the gains from trade than the other. The long-studied model of conflict called “the game of chicken” provides a useful analogy. In the game of chicken, two players must decide between aggressive and cooperative strategies. Mutual selection of cooperative strategies provides reasonably good payoffs for both. But each player is better off selecting an aggressive strategy when faced with an opponent who cooperates. In this situation, the cooperator suffers. The critical difference between “chicken” and the “prisoner’s dilemma” is that the cooperator does not benefit from switching to an aggressive strategy when faced by an aggressive strategy. If both players select the aggressive strategy, both suffer enormous losses.

Figure 7.1 illustrates the payoffs for a simple version of the game of chicken. The two pure strategy Nash equilibria of the game are (Mercantilism, Free Trade) and (Free Trade, Mercantilism). If the United States chooses free trade and China chooses mercantilism, then the United States gets a payoff of one and China gets a payoff of six. But the United States has no incentive to switch to mercantilism itself (the payoff of this switch is zero)… In this game there are enough mutual advantages to trade that in equilibrium neither country wants to respond to mercantilism with mercantilism (the payoff of one is better than zero), but the benefits of trade are not distributed equally between the trading partners. Mutual free trade (which would have the highest overall payoffs) is the cooperative strategy, but it is not a Nash Equilibrium.

The long-term result of unilateral free trade with a mercantalist is, they make clear, disastrous for the free trading party:

For the last several decades, the United States has generally played a cooperative strategy on trade with China and other mercantilists. U.S. markets have been open to Chinese goods, and the United States supported Chinese membership in the World Trade Organization. American leaders selected free trade on the basis of the (false) hope that China would reciprocate by opening its markets to American firms. China, by contrast, has pursued an aggressive mercantilist strategy.

If the payoffs for mercantilism are indeed similar to those from the game of chicken, then it is obvious that China has no incentive whatsoever to voluntarily shift from exploitation to cooperation (a payoff of six is better than a payoff of five). As discussed in previous chapters, the fruits of mercantilist exploitation are evident. Many products developed in the United States are now produced almost entirely in China. The United States runs a large trade deficit with China on both high tech products and traditional industries like clothing and shoes. Meanwhile, in 2012 China purchased only about thirty two cents worth of goods and services from the United States for every dollar of goods and services that Americans bought from China. In return for Chinese products, Americans go ever deeper into debt.

The Richmans then build on this game theoretic model to develop their own proposal:

To get to the objective of free and balanced trade (mutual free trade), the U.S. government must adopt a game-changing strategy that provides mercantilists with incentives to cooperate in return for American cooperation. A cooperative pattern cannot be sustained unless the United States adopts strategies that provide all parties with incentives to sustain it. Sustaining cooperation requires the use of credible threats and promises that transform the incentives of the other player… In practical terms, what should such a strategy be and accomplish?

- It should be effective. A strategy that doesn’t balance trade fails to accomplish the primary objective. A strategy that depends upon unrealistic assumptions about the actions of other nations will not accomplish the objective of balancing trade.

- It should be efficient. The cost of implementation should be low, and the risks of undesirable or unanticipated side effects should be low or manageable. It should lead to a free trade–free trade outcome not a mercantilism–mercantilism outcome.

- It should be as consistent as possible with international law. Strategies that violate international law risk wrecking good aspects of the international trading system along with problematic ones. They would also be much more difficult and costly to implement and sustain.

- It should be targeted at imbalanced trading relationships. In 2012 the United States ran a more than twenty billion dollar trade surplus in goods with Australia. Australia clearly is not part of the U.S. trade balance problem, so targeting Australia in any way would be gratuitous and counter-productive in the effort to balance trade.

The remainder of the book is devoted to the presentation and analysis of a number of different policy proposals. Among the policies they evaluate are currency rate reform, such as the 2009-2001 Currency Reform for Fair Trade Act; the national strategic tariff proposed by Ian Fletcher in his book Free Trade Doesn’t Work (which I’ve written about and recommended in my own policy proposals); restrictions on foreign asset purchases to adjust the flow of foreign capital; the use of countervailing currency limitations to balance trade; and cap-and-trade style import certificates, famously recommended by Warren Buffett.

After rejecting each of these for various reasons, they propose their own solution: The scaled tariff. The Richmans explain their policy like this:

The Scaled Tariff is a single-country variable tariff whose rate rises as the trade deficit increases and falls as trade becomes more balanced. It is a tariff upon all the goods being imported by a trade deficit country from a trade surplus country. No particular product is protected; the Scaled Tariff simply changes the terms of trade between the two countries much as currency devaluation would change the terms of trade with all countries. By targeting countries with which the United States has a large trade deficit, the Scaled Tariff would efficiently, legally, and effectively balance trade. It would be applied to all imported goods from trade surplus countries that have had a sizable trade surplus with the United States over the most recent four economic quarters.

The tariff rate would cause the revenue taken in by the duty upon imported goods from the particular country to equal 50 percent of the trade deficit (goods plus services) with that country.

The Richmans provide the following example:

In 2012 the United States imported $440 billion of goods and services from China, while China imported $112 billion of goods and services from the United States, creating a trade deficit of $298 billion. An initial tariff rate of 35 percent on $427 billion of imported goods from China would be designed to collect $149 billion (50 percent of $298 billion) in tariff revenue.

Now, let’s compare the Richmans’ approach to the Liberation Day tariff formula that Surowiecki called “extraordinary nonsense”. The Liberation Day tariff formula takes the US trade deficit with that country and dividing it by the value of the country’s exports to the United States, then divides that value in half. For instance, if China had a trade deficit with the US of $298 billion, and exports of $427 billion, then 0.5 x $298 billion / $427 billion) ~ 35%.

Do you see? Trump’s Liberation Day tariffs are are calculated with the exact same formula as the Richmans’ scaled tariffs.

In fact, if you read Trump’s executive order, it reads as if it was written by the Richmans – or at least by someone with a copy of their book on their desk as they typed the executive order. If you compare Trump’s executive order to pages 8-11 of Balanced Trade you’ll see it for yourself. Rarely in the history of presidential policy has a scholars policy formulation been so precisely followed.

The only difference is that Trump has also included a national strategic tariff of 10% as a baseline. Trump trade policy is simply Ian Fletcher’s Free Trade Doesn’t Work combined with the Richmans’ Balanced Trade!

Why Is the Scaled Tariff Preferable to the National Strategic Tariff?

Since I’ve referenced Ian Fletcher’s work on three different occasions on this blog, it seems worthwhile to offer some explanation on why the White House might have favored the Richmans’ scaled tariff over Fletcher’s national strategic tariff.

Here’s the explanation that the Richmans offer as to why the scaled tariff is better than a flat national tariff or targeted country-specific tariffs:

The Scaled Tariff is nearly immune to counter-tariffs. Any country that enacts a counter-tariff would be increasing the U.S. tariff on its products. Instead of starting a trade war, the Scaled Tariff would provide automatic responses that would end the trade war that is currently being conducted upon the United States by the mercantilist countries. In terms of the game of chicken example developed in chapter 7, the Scaled Tariff is equivalent to a policy that automatically responds to the competitor’s move with the identical move. In the face of such a policy, the response with highest payoffs for trading partners is to cooperate by reducing trade manipulations.

The Scaled Tariff specifically and exclusively targets countries which are running trade surpluses with the United States . Thus, it specifically creates incentives for these countries to take steps to shift their trade toward balance by stimulating their domestic economies, removing tariff and non-tariff barriers, ending currency manipulations, and so forth. It avoids targeting trade relations with countries that are not contributors to global current account imbalances.

In other words, the national strategic tariff imposes barriers to trade that stay in place even when trade is fair and balanced. The scaled tariff drops to 0 when trade is balanced. In contrast, a national strategic tariff always stays in place, which means that gains from trade are reduced even by equitable partners.

The difference between the two is fundamentally a difference in priorities. Fletcher prioritizes protection of key industry, while the Richmans emphasize reciprocity in trade flows. The Trump Administration has hedged its position – it’s adopted the scaled tariff in full, but with a low 10% national strategic tariff (Fletcher recommended 25%).

But are the Liberation Day tariffs actually reciprocal?

Many critics of Trump tariff plan are complaining that the Liberation Day tariffs aren’t actually “reciprocal” tariffs because they aren’t set at the same rate as the trading party’s tariffs.

Both the Richmans’ book and the Trump Administration’s executive order offer the same answer here. Since the goal is not to achieve “free trade”, it is to achieve balanced trade, therefore the method by which this is achieved is not “reciprocity of tariffs” but reciprocity of trade flows.

The balance of trade can be and is disrupted by non-tariff policy as much or more than by tariff policy. Balanced Trade puts it this way:

Japan, China, and a variety of other U.S. competitors found ways to exploit U.S. free trade ideology. By pursuing policies such as currency manipulation, export subsidies, and non-tariff barriers, they created effective barriers to trade without depending principally on tariffs. Trade was brought and kept out of balance, and U.S. manufacturing prominence across many industries was destroyed.

The Trump EO puts it like this:

Non-tariff barriers deprive U.S. manufacturers of reciprocal access to markets around the world. The 2025 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers (NTE) details a great number of non-tariff barriers to U.S. exports around the world on a trading-partner by trading-partner basis. These barriers include import barriers and licensing restrictions; customs barriers and shortcomings in trade facilitation; technical barriers to trade (e.g., unnecessarily trade restrictive standards, conformity assessment procedures, or technical regulations); sanitary and phytosanitary measures that unnecessarily restrict trade without furthering safety objectives; inadequate patent, copyright, trade secret, and trademark regimes and inadequate enforcement of intellectual property rights; discriminatory licensing requirements or regulatory standards; barriers to cross-border data flows and discriminatory practices affecting trade in digital products; investment barriers; subsidies; anti-competitive practices; discrimination in favor of domestic state-owned enterprises, and failures by governments in protecting labor and environment standards; bribery; and corruption.

Moreover, non-tariff barriers include the domestic economic policies and practices of our trading partners, including currency practices and value-added taxes, and their associated market distortions, that suppress domestic consumption and boost exports to the United States. This lack of reciprocity is apparent in the fact that the share of consumption to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the United States is about 68 percent, but it is much lower in others like Ireland (27 percent), Singapore (31 percent), China (39 percent), South Korea (49 percent), and Germany (50 percent).

Why not directly reciprocate tactic-by-tactic country-by-country? That would be incredibly inefficient and virtually impossible. The mix of tactics employed by any given mercantilist will depend on its particular geography, debt, industry, and population. The US couldn’t “reciprocate” such policies even if it tried, because they are unique to the context of each economic actor.

Instead, the scaled tariff reciprocates against all of these tactics easily and effectively. When trade is balanced, tariffs go to zero (or to 10%, in the Trump version). It’s clean, it’s efficient, and it’s effective. Thus, Trump’s tariffs are reciprocal tariffs – but what they reciprocate against is unfair trade practice in generally, evidenced by an imbalance of trade, and not tariffs specifically.

So there you have it. Far from being “extraordinary nonsense,” Trump’s trade policy is in fact a careful implementation of trade policies that have been developed and detailed at book-length. And it is based in part on work by thinkers that we’ve approvingly cited here at the blog, such as Ian Fletcher.

Contemplate this on the Tree of Woe.

Contemplations on the Tree of Woe has imposed a scaled tariff on all subscribers from the Territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands. To liberate the resident penguins from the pernicious burden of my tariff regime, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.